Farro

A revered heirloom grain, farro is essentially an unhybridized ancestor of modern wheat. Gianluigi Peduzzi of Rustichella d'Abruzzo works alongside a group of local farmers who cultivate the local variety farro vestino over just 50 hectares between Penne and the Gran Sasso, the highest peak of the Apennines. Farro thrives in this stony, well-drained soil—without the use of fertilizers.

Farro

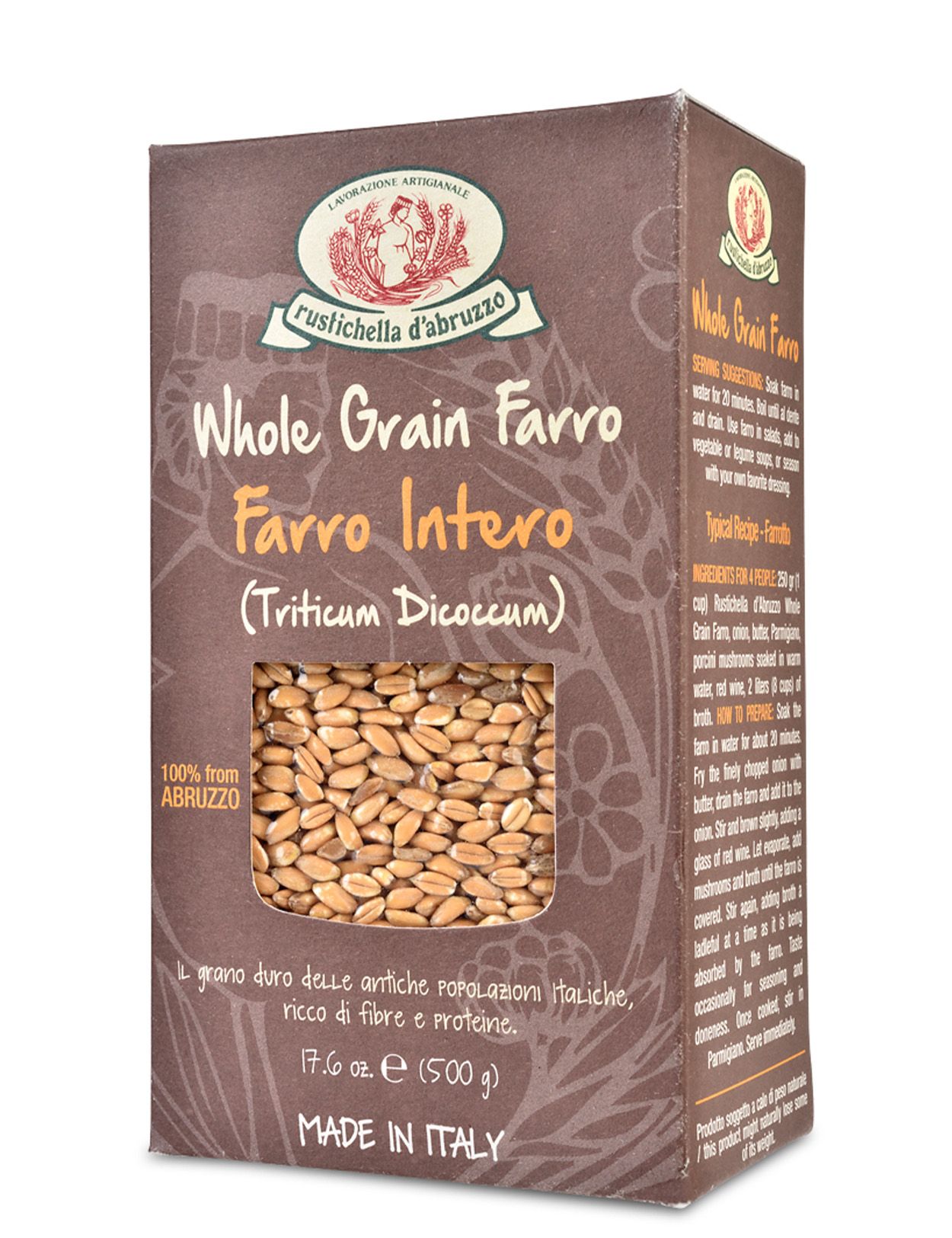

In Italy, Farro is the overarching term used for einkorn, emmer and spelt, (also known as farro piccolo, farro medio, and farro grande), each a subspecies of the genus Triticum (wheat), each with a different genetic makeup. Farro is essentially an unhybridized ancestor of modern wheat (whereas barley is of a different genus altogether, and neither a species nor a subspecies of wheat.)

• Farro Grande: Spelt (Triticum aestivum spelta) is a subspecies of Triticum aestivum, which includes common bread wheat (Triticum aestivum aestivum).

• Farro Piccolo: Einkorn (Triticum monococcum monococcum) is a subspecies of Triticum monococcum.

• Farro Medio: Emmer (Triticum turgidum dioccum) is a subspecies of Triticum turgidum, which includes durum wheat. It is the primary farro grain planted in Italy (Abruzzo included) and it is considered to be of a higher quality for cooking than spelt or einkorn.

Farro findings have been reported from archeological sites in Neolithic Egypt, Turkey, and early Bronze Age Mesopotamia. Ancient rabbinic literature cites farro as one of the five grains to be used during Passover as matzah. The ancient Romans cultivated the grain in the Italian peninsula where it became “far” or “gran far,” which was milled into “puls” to make a dish very similar to today’s polenta. Farro is believed to have fed the Roman legions, given as a ration to each solider in small bags from which they made food or fermented it with water to make a type of beer. Farro has been cultivated in Italy since the time of the ancient Romans, but unfortunately lost its position with the advent of the intensive modern wheat agriculture after the World Wars, and the “invention” of modern wheat. Lately, however, farro is experiencing a renaissance because of its small-scale farming methods, high nutritional value, very low gluten count, and wonderful flavor and texture. In Italy today, farro is cultivated in a very small area around the foothills of both sides of the central Apennines—mainly in Tuscany, Umbria, Marche and Abruzzo—about 1,000 feet above sea level. It is planted in October and harvested in June.